With food bloggers and Instagrammers being accused of promoting the rise of so-called ‘clean eating’, Celia Jarvis explores how negative emotions such as guilt around ‘wrong’ foods could be a sign of what some consider to be a new kind of eating disorder.

This article has been adapted since being published in print in the Summer 2017 issue of Optimum Nutrition magazine.

It’s 7am in East London, and Pinakin Patel has just completed an hour of yoga and now he’s ready for his breakfast.

Like every other morning, Pinakin will start his day with a glass of orange juice, followed by fresh fruit and then some dried fruit.

For his 11am snack he’ll enjoy a carrot, cucumber and broccoli salad, finished off with five almonds, five cashew nuts and exactly 10 black grapes.

At around midday Pinakin will have his last meal of the day, a vegetable curry, before heading out for a five-mile walk.

While Pinakin may seem to be trying to eat extremely healthily, could he be crossing the line towards orthorexia nervosa?

What is orthorexia?

Orthorexia, from orthos meaning ‘straight’ or ‘right’ and orexis meaning ‘appetite’, is literally the fixation on correct eating.

The term was first coined in 1997, in an essay written by Dr Steven Bratman for Yoga Journal.

Bratman described it as: “an unhealthy fixation with what the individual considers to be healthy eating.”

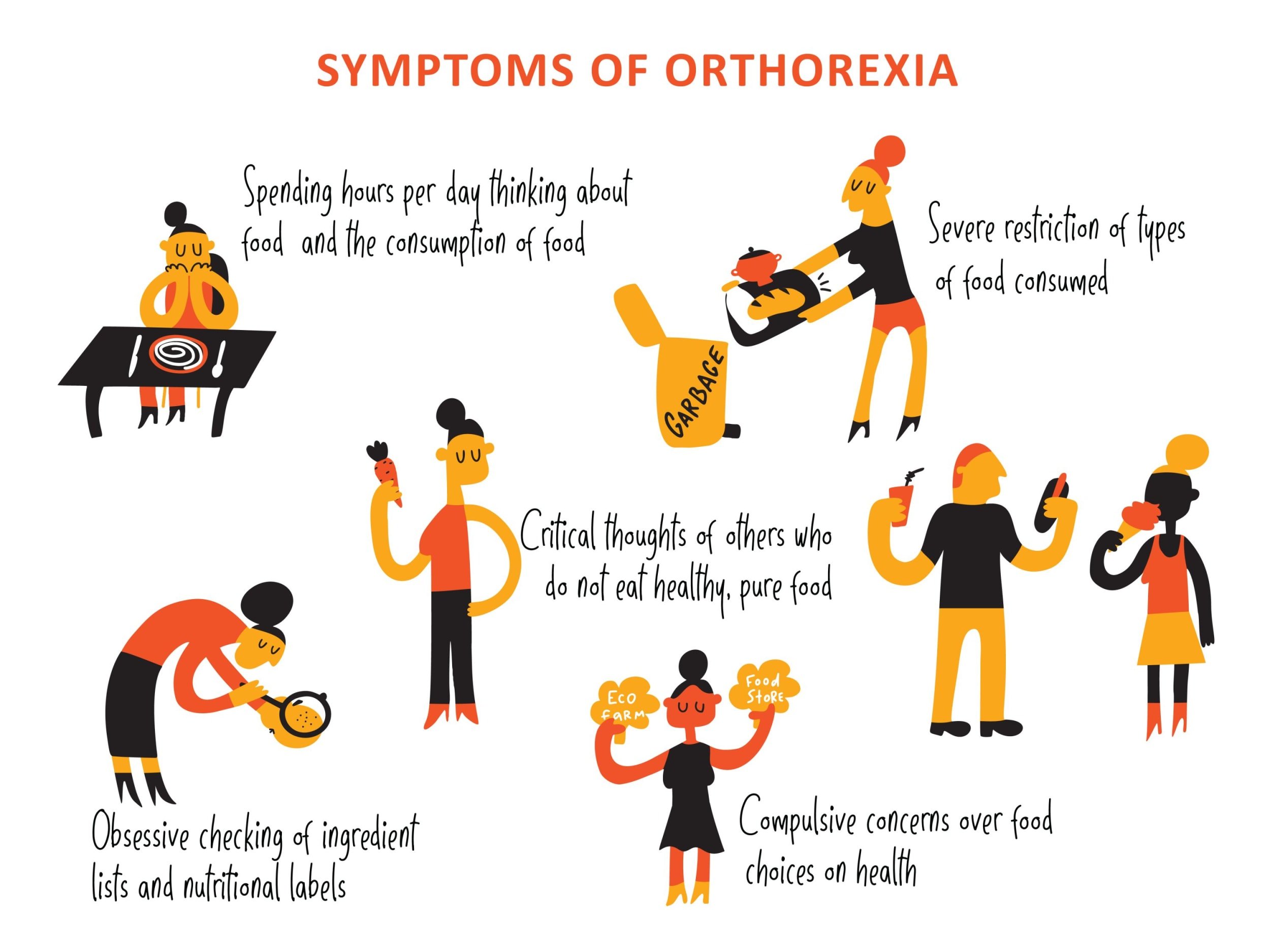

Orthorexia usually starts with the desire to cut out foods considered to be unhealthy, such as processed, sugary or fatty foods, and increase the intake of fresh foods.

However, the problem begins when healthy eating turns obsessive and the list of forbidden foods gets longer.

Refined carbohydrates, dairy, sugar and meat are commonly removed from the diet. Fruit and vegetables remain but, in some cases, only if they’re organic, locally grown and GM-free.

Such a restricted diet inevitably leads to weight-loss. However, unlike anorexia and bulimia, the focus of orthorexia is on healthy eating and any weight-loss is incidental.

Orthorexia: the risks and dangers

We could ask: what is so wrong with this? As the population gets more obese and less healthy, surely any attempt at healthy eating can’t be a bad thing.

Yet despite any possible benefits, there are potential negative side effects for a person gripped by orthorexia.

Social isolation is one. They may begin to dread and avoid group gatherings which revolve around enjoying rich, calorific food and drink.

In Health Food Junkies, Bratman writes: “Eventually orthorexia reaches a point at which the orthorexic devotes much of her life to planning, purchasing, preparing and eating meals”.

How to spot orthorexia

For Pinakin Patel, though, social occasions pose no problems. “I’m not always this rigid, it’s important for me to enjoy myself sometimes, especially around birthday parties,” he says.

“I’ll eat chocolate cake — enjoy it, finish it and then never think of it again. There’s no guilt for me.”

Pinakin’s relaxed attitude on digressing from his normal diet would be unusual for someone with orthorexia.

There is no single universally accepted diagnostic criteria for the condition – nor even an accepted definition of orthorexia.

However, it is generally agreed that people with orthorexia display obsession or pathological preoccupation with healthy nutrition; there are emotional consequences to breaking self-imposed nutritional rules; and that their relationship with food and health was having negative consequences on their mental and physical health.

Bratman himself came up with an ‘authorised orthorexia self-test’ comprised of a series of questions to determine whether a person could be described as orthorexic.

For example, a question might be: ‘When I eat any food, I regard to be unhealthy, I feel anxious, guilty, impure, unclean and defiled.’

A ‘yes’ response to a certain amount of these questions could suggest the individual might have orthorexia. Pinakin took one of these tests and replied negatively to all six questions, indicating that he is not orthorexic.

Orthorexia vs healthy eating

But Rebecca Jennings, from Horsham-based Love to Eat Nutrition, says she sees plenty of people who are.

“I’ve seen a rise in people coming to me with orthorexia and I think it takes a lot for people to admit to actually being orthorexic.

“From experience, people perceive themselves as making healthy choices and wanting to look after their body by providing it with ‘nourishing foods’.

“Being mindful about nutrition is great, but not being able to eat food without suffering guilt is when it becomes a problem.

“Someone who’s just a healthy eater would be able to take a break from their routine and eat a brownie and have no qualms about it.

“Whereas someone who is orthorexic would feel guilty about having something ‘unhealthy’.”

Deanne Jade, psychologist and founder of the National Centre for Eating Disorders expands on this.

“Orthorexia is not just a description of behaviour,” she says. “It is really about underlying motivations and the need for some people to escape from their fears by controlling the food they eat.

“If a person becomes obsessive about healthy eating and feels fearful or guilty if they have to deviate from that plan, then this may suggest a move from healthy eating to orthorexia.”

And it is these emotions of regret, fear and shame that are recurring themes within the orthorexic’s relationship to food, with individuals experiencing “guilt and self-loathing when they commit food transgressions”.

Why orthorexia thrives on Instagram

There is also some evidence to suggest that the media may have an influence on orthorexia. A study published in March 2017 found that Instagram users who follow accounts devoted to health and healthy eating, are significantly more likely to develop orthorexia than the rest of the population.

The study asked 680 participants, all of whom followed Instagram health accounts, to complete a multiple-choice questionnaire called the ORTO-15; a 15-point questionnaire used to diagnose orthorexia.

Typical questions included: ‘Does the thought of eating food worry you for more than three hours a day?’ Or: ‘Do you feel guilty when transgressing from your usual diet?’

The study found that orthorexia nervosa was significantly higher in the Instagram group, with an incidence of 49% compared to just 1% in the general population.

The study has not yet been peer-reviewed, however, and a correlation isn’t a causation. Common sense also suggests that orthorexics may simply be more inclined to seek out healthy food images.

Nevertheless, a quick flick through Instagram shows how influential it could be, with picture after picture of what appear to be perfect, healthy lives on show, with exotic salads in earthenware bowls, manicured nails clutching green juices, and inspirational mottos transposed against sunsets.

Orthorexia linked to a culture of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ eating

But it’s not just Instagrammers who stand accused of encouraging unhealthy eating habits.

So-called ‘clean-eating’ cookbooks have also been vilified for encouraging unhealthy, restrictive diets — with almost no distinction made between books produced by bloggers-turned-celebrity-chefs and qualified nutritional therapists who are signed up to BANT, the profession’s regulatory body.

So, what do health professionals have to say about the role the media play in potentially creating and promoting orthorexia?

Psychologist Deanne Jade admits it’s a complex subject, but believes the media are partly responsible for perpetuating orthorexia.

“The media and social media will do anything for a story, no matter what the cost,” she says.

Rebecca Jennings elaborates. “I definitely think the media has a part in creating orthorexia,” she says.

“Being healthy has become cool recently; it’s seen as looking after yourself, so a lot of brands are using buzz words like ‘clean’, ‘healthy’ and ‘guilt-free’ which girls have latched on to.

“Body image has always been big in the media. Certain newspapers will compliment celebrities for looking slim in a bikini and ‘fat shame’ others who don’t.

“I think when girls feel like it’s okay for newspapers to make judgements on others, then they feel others make judgements on them and they become hugely self-critical.”

Orthorexia remains an uncategorised disorder

Currently, despite its apparent rise in prevalence, there are relatively few studies into orthorexia, and so it remains unclassified as an eating disorder by the American Psychiatric Association.

This makes its incidence hard to understand. One argument against categorisation as an eating disorder is that it doesn’t include the main characteristics of anorexia and bulimia, namely, the immense fear of becoming fat, extreme weight control behaviour and over-estimation of weight.

However, some experts agree that orthorexia not only has similarities with eating disorders but also that “orthorexia and anorexia share common traits of perfectionism, high trait anxiety, and a high need to exert control”.

Another similarity between orthorexic and anorexic individuals is the tendency towards being achievement-oriented, so that sticking to a particular diet is seen as a mark of self-discipline while breaking the diet is seen as loss of self-control.

Similar to individuals with OCD, orthorexics have also been found to “manifest certain obsessive–compulsive tendencies such as recurrent, intrusive thoughts about food and health at inappropriate times, inflated concern over contamination and impurity, and a strong need to arrange food and eat in a ritualized manner”.

Orthorexia is often about control

Blogger and recovering orthorexic Jordan Younger recognises her own challenges around compulsive tendencies as she struggles to adjust to a more relaxed diet, writing: “It’s torture! And I have very little control over it.

“For someone who spiralled downward into orthorexia because I like to have control in all areas of my life, this lack of control has been frustrating and debilitating.

“I am trying to stay focused because I know change doesn’t happen overnight. I know that the more I obsess, the greater the problems I am causing for myself.

“And I know that reverting back to my old habits of restriction will only make things harder on me in the end.”

Orthorexia’s impact and how to seek support

But regardless of how orthorexia is categorised, whether as an eating disorder or OCD, the impact for people living with it can be severe.

Aside from potential medical problems if a diet becomes overly restricted, orthorexia sufferers also experience mental health issues including anxiety and social isolation.

Psychologist Deanne Jade has advice if you suspect someone close to you is dealing with orthorexia.

“With the right support, recovery from orthorexia is possible and options are available,” she says. “I would suggest, in the first instance, that you talk to the person and encourage them to seek specialist, confidential help.

“A good, trustful relationship with a therapist is probably the most important part of recovery. A therapist who’s trained in eating disorders will be able to understand.”

For further advice visit the National Centre for Eating Disorders. Alternatively Beat, the eating disorders charity, has a helpline open 365 days, 4pm to 10pm. Call 0808 801 0677.

When healthy eating becomes obsessive

“I wouldn’t consider myself to be an orthorexic,” says Julie, pausing for thought. “But it did get to the stage where I was thinking about nearly everything that passed my lips.”

Julie, 25, successfully lost weight after discovering that she was on the verge of developing type 2 diabetes.

“My mum had diabetes and was really sick with it, so when I was told I was in danger of developing it too, my reaction was no way!

“It’s funny how I could go from being really relaxed about food, regularly eating takeaways and not thinking about the consequences, to being really strict to the point that I would make a mental judgement before eating anything.”

As her health improved, Julie says she became even more rigid in her diet. “I started off by cutting out takeaways and obvious junk but then I started looking at everything and deciding whether it fell into a healthy category or not.”

It was when Julie began to feel unhappy and stressed around food that she realised that she might be developing a problem.

“If I was in a situation where I had no control over what I could eat and had to eat something I considered to be unhealthy, I would feel miserable. Sometimes I would even feel angry.”

But she feared that if she gave up control, she would lapse into old habits.

“Eventually, what I realised was that, for me, my growing need to control my diet was not that different to my need to control other aspects of my life.

“To overcome the negative emotions that went along with that, I took up meditation. That really helped me to de-stress and once I was less stressed in general, I found it easier to be more relaxed about food.”

Julie does still have a healthy diet but says she no longer obsesses about what foods are right or wrong.

“There are a lot of things I don’t eat — I don’t eat fast food, despite once eating it several times a week.

“But if there really was nothing else available — and this has happened — I would eat it. I wouldn’t feel angry or upset about it, though. I’d just move on.”

Enjoyed this article?

Learn about semaglutide and the pros and cons of weight-loss medication

For articles and recipes subscribe to the Optimum Nutrition newsletter

Discover our courses in nutrition